Tine Returns from Her Time Travels

Tine hasn't been seen on her daily walks for a while, and some villagers (who set their clocks by her daily walks with Rubob) most likely assumed that she was away. If by "away" they meant away from the village, they were mistaken.

Tine leaves the village only with great reluctance, and she's managed to stay very much within it recently. And yet, curiously enough, she arrived back among the villagers yesterday afternoon, at about 2 o'clock.

Tine, you see, has been time traveling. For the past few weeks, she's remained very much within the here portion of the here and now, but not within the now. Tine's been preoccupied at home, poring over dusty old documents, digging into her village's past.

Tine's time mechanism

But she resurfaced yesterday, as it happened, on a walk with Rubob. It was a bright, warm day -- all very summery for a change. Even so, she was very much lost in her thoughts, as she has been for weeks. The two were crossing Main Street when Rubob stopped short to look at a house -- well not so much a house, but a cottage.

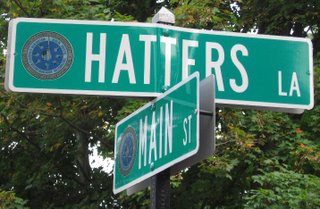

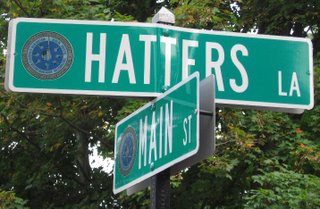

"Did you know that it was once a hat shop -- in the late 1700s," Tine said to Rubob. "That's why Hatters Lane is called, well, Hatters Lane."

They had just walked down the narrow lane to the cottage.

"Yes, Tine, I think you did say something about that recently," Rubob said. Tine had talked of little else for some time. This house was occupied by so and so, and interestingly enough, that house was at one time a such and such. "Quite remarkable," Rubob said.

"And a barber had a shop there, too, around 1850," Tine continued. "And after that, a Barbour owned it, funnily enough -- not a barber, but a Barbour, one Henry Barbour. And let me see -- it was an antiques shop as well. Did you know that, Rubob?"

"And a barber had a shop there, too, around 1850," Tine continued. "And after that, a Barbour owned it, funnily enough -- not a barber, but a Barbour, one Henry Barbour. And let me see -- it was an antiques shop as well. Did you know that, Rubob?"

Rubob didn't reply. He was looking at the cottages rather quizzically, with his head cocked to one side.

"And Wilmarth Sheldon Lewis, that scholar of all things English, he was a customer of the antiques store. I don't suppose you knew that, did you?" Tine asked. Tine thought she might get Rubob's attention with the mention of Wilmarth -- known to his friends as "Lefty," understandably enough (Wilmarth?).

But Rubob was lost in his thoughts, as he often is.

"It looks a little crooked," Rubob said. "Is that house leaning to one side?"

"Lefty said the antiques shop owners had excellent taste but weren't very good at running a business," Tine said. "They revived an interest in Victorian bric-a-brac, Lefty wrote in 'One Man's Education.' You like bric-a-brac, don't you?"

Rubob, as Tine knows, doesn't much care for bric-a-brac, but in any case he wasn't listening. He was squinting at the cottage, standing well back from it, with his feet planted dangerously in the town's busy main thoroughfare. He was leaning considerably to port, with his head tilted the same way.

"It's definitely a little crooked," Rubob said. "Take a look."

"I think we should get back on the sidewalk," Tine said, "but OK." She cocked her head a little to the left, tilted it back the other way, and agreed with Rubob. "It's crooked," she said -- "a crooked house. Probably a crooked antiques store, too."

"A crooked what?" Rubob asked.

"Antiques store," Tine said. "You know, where Lefty shopped. He bought furniture for his house there."

"Who's Lefty?" Rubob asked.

"Wilmarth," Tine replied. "You know, Lefty. He was named by his Yale pals after Lefty Louie, a New York gangster. Lefty was just Lewie before Lefty Louie came along."

"He did?" Rubob asked. "Wilmarth Lewis really bought antiques there?" Rubob had read all about the Lewis Walpole Library -- containing Lewis' collection of Horace Walpole's letters and artwork -- and he'd visited it several times, but evidently he'd missed this fact.

Lefty Lewis' house

"He did, Rubob," Tine said. "He bought some of his grand furniture in this little cottage. I'm sure he paid too much, if you're convinced they were crooked."

"But really, Tine, I'd never noticed that the cottage was leaning so much," Rubob said.

"It's disorienting looking at it too long," Tine said. "I can't tell whether it's crooked or whether it's the neighboring cottage that's a little off."

"It's the left one, Tine -- only the left one that's leaning," Rubob said.

"I'm not so sure," Tine said. "I'm not so sure about anything these days. These cottages throw me back in time and leave my head in a whirl. You know, it's all my historical research -- it's left me not knowing what century I'm in when I'm walking around in the village. My head reels from it all."

"H. G. Wells said that the sensations of time travel are 'excessively unpleasant,' " Tine continued. "He talked of a 'helpless headlong motion,' a feeling of 'an imminent smash.' Well, I don't know about that. I'm inclined to think that time travel can be rather pleasant -- at times at least. Even Wells goes on to write about misty landscapes, puffs of vapor, and white snow fading into the bright green of spring in an instant -- that sort of thing, you know ['sor' o' thing,' she added to herself, quoting Chef Blackstock]. It sounds not unlike our walks through the village together, Rubob."

"But still," Tine said, "it's true that I've been caught up in the headlong whirl of my time travels. H. G. Wells writes about an 'eddying murmur' and a 'strange dumb confusedness' after he shifts his machine into gear. I think he must have done a bit of historical research himself. I must say that it's rather agreeable being out on a walk for a change, back in the here and now, just standing here admiring your crooked cottage. "

And it was, all in all, a very pleasant walk, Rubob had to agree -- even with the old cottage's foundation clearly sinking into the ground.

Tine leaves the village only with great reluctance, and she's managed to stay very much within it recently. And yet, curiously enough, she arrived back among the villagers yesterday afternoon, at about 2 o'clock.

Tine, you see, has been time traveling. For the past few weeks, she's remained very much within the here portion of the here and now, but not within the now. Tine's been preoccupied at home, poring over dusty old documents, digging into her village's past.

Tine's time mechanism

But she resurfaced yesterday, as it happened, on a walk with Rubob. It was a bright, warm day -- all very summery for a change. Even so, she was very much lost in her thoughts, as she has been for weeks. The two were crossing Main Street when Rubob stopped short to look at a house -- well not so much a house, but a cottage.

"Did you know that it was once a hat shop -- in the late 1700s," Tine said to Rubob. "That's why Hatters Lane is called, well, Hatters Lane."

They had just walked down the narrow lane to the cottage.

"Yes, Tine, I think you did say something about that recently," Rubob said. Tine had talked of little else for some time. This house was occupied by so and so, and interestingly enough, that house was at one time a such and such. "Quite remarkable," Rubob said.

"And a barber had a shop there, too, around 1850," Tine continued. "And after that, a Barbour owned it, funnily enough -- not a barber, but a Barbour, one Henry Barbour. And let me see -- it was an antiques shop as well. Did you know that, Rubob?"

"And a barber had a shop there, too, around 1850," Tine continued. "And after that, a Barbour owned it, funnily enough -- not a barber, but a Barbour, one Henry Barbour. And let me see -- it was an antiques shop as well. Did you know that, Rubob?"Rubob didn't reply. He was looking at the cottages rather quizzically, with his head cocked to one side.

"And Wilmarth Sheldon Lewis, that scholar of all things English, he was a customer of the antiques store. I don't suppose you knew that, did you?" Tine asked. Tine thought she might get Rubob's attention with the mention of Wilmarth -- known to his friends as "Lefty," understandably enough (Wilmarth?).

But Rubob was lost in his thoughts, as he often is.

"It looks a little crooked," Rubob said. "Is that house leaning to one side?"

"Lefty said the antiques shop owners had excellent taste but weren't very good at running a business," Tine said. "They revived an interest in Victorian bric-a-brac, Lefty wrote in 'One Man's Education.' You like bric-a-brac, don't you?"

Rubob, as Tine knows, doesn't much care for bric-a-brac, but in any case he wasn't listening. He was squinting at the cottage, standing well back from it, with his feet planted dangerously in the town's busy main thoroughfare. He was leaning considerably to port, with his head tilted the same way.

"It's definitely a little crooked," Rubob said. "Take a look."

"I think we should get back on the sidewalk," Tine said, "but OK." She cocked her head a little to the left, tilted it back the other way, and agreed with Rubob. "It's crooked," she said -- "a crooked house. Probably a crooked antiques store, too."

"A crooked what?" Rubob asked.

"Antiques store," Tine said. "You know, where Lefty shopped. He bought furniture for his house there."

"Who's Lefty?" Rubob asked.

"Wilmarth," Tine replied. "You know, Lefty. He was named by his Yale pals after Lefty Louie, a New York gangster. Lefty was just Lewie before Lefty Louie came along."

"He did?" Rubob asked. "Wilmarth Lewis really bought antiques there?" Rubob had read all about the Lewis Walpole Library -- containing Lewis' collection of Horace Walpole's letters and artwork -- and he'd visited it several times, but evidently he'd missed this fact.

Lefty Lewis' house

"He did, Rubob," Tine said. "He bought some of his grand furniture in this little cottage. I'm sure he paid too much, if you're convinced they were crooked."

"But really, Tine, I'd never noticed that the cottage was leaning so much," Rubob said.

"It's disorienting looking at it too long," Tine said. "I can't tell whether it's crooked or whether it's the neighboring cottage that's a little off."

"It's the left one, Tine -- only the left one that's leaning," Rubob said.

"I'm not so sure," Tine said. "I'm not so sure about anything these days. These cottages throw me back in time and leave my head in a whirl. You know, it's all my historical research -- it's left me not knowing what century I'm in when I'm walking around in the village. My head reels from it all."

"H. G. Wells said that the sensations of time travel are 'excessively unpleasant,' " Tine continued. "He talked of a 'helpless headlong motion,' a feeling of 'an imminent smash.' Well, I don't know about that. I'm inclined to think that time travel can be rather pleasant -- at times at least. Even Wells goes on to write about misty landscapes, puffs of vapor, and white snow fading into the bright green of spring in an instant -- that sort of thing, you know ['sor' o' thing,' she added to herself, quoting Chef Blackstock]. It sounds not unlike our walks through the village together, Rubob."

"But still," Tine said, "it's true that I've been caught up in the headlong whirl of my time travels. H. G. Wells writes about an 'eddying murmur' and a 'strange dumb confusedness' after he shifts his machine into gear. I think he must have done a bit of historical research himself. I must say that it's rather agreeable being out on a walk for a change, back in the here and now, just standing here admiring your crooked cottage. "

And it was, all in all, a very pleasant walk, Rubob had to agree -- even with the old cottage's foundation clearly sinking into the ground.

<< Home