One Hundred Percent Chance of Ice Pellets

As Tine lay in bed tonight preparing to fall asleep, she thought, as she often does, about her afternoon walk. When she thinks late at night, Tine's thoughts aren't so much about the things she sees on her walk; they are the things she sees on her walk. Just as Tine became old Fred Jones' sculpture when she looked at old Fred Jones' sculpture, or as Charles Schultz became a blade of grass when he drew a blade of grass, Tine became a doorway when she thought of a doorway, or a round stone in a stone wall when she thought of a round stone in a stone wall.

That might sound repetitive, and so it should, because that's really what it is: repetitive. Tine's mind at bedtime becomes something like a minature replicator. Bits and pieces of Tine's walk repeated themselves all over again as she dozed off in her warm bed, seeming every bit as real and filling up her mind every bit as much as they did during her afternoon walk. "Have you ever looked at a cabbage in the moonlight," Tine thought. "Well, it's such a lovely, astounding, leafy, bountiful thing, taking shape in the dark soil under the moonlight, that the mind itself can't help feeling itself become a cabbage in the moonlight for a moment."

It might seem that Tine was overly weary and overly chilly again, as she often is after long winter walks, and that her mind was wandering aimlessly again (or "aimessly," as Tine thought sleepily) . But while she was weary, she wasn't overly weary. She was comfortably weary, because she was in her cozy bed. If she had explained it to Rubob, she might have said that she was appropriately weary, perhaps seventy percent weary (because Rubob sensibly likes to quantify things). And she definitely wasn't chilly; she was warm and content. And what's more, she knew exactly what she was thinking; her mind may have been wandering, but not aimessly. A mind, like the moon, or even like a walker, is expected to wander; it's part of being a mind. Thoughts of cabbages in the moonlight led to thoughts of doorways in the daylight, of pendants (those things over doorways on garrison Colonials), of stones (those things in walls), and of holiday ornaments (those "hideous" things, as Rubob might say if he was in a Scrooge-like frame of mind).

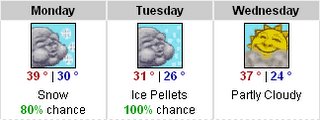

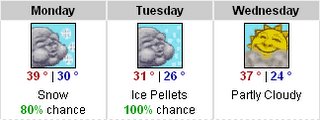

All these pleasant images, these late-night conjurings in Tine's bed, were chased aside, though, when Tine's thoughts turned to where her walk might take her tomorrow. She recalled the long-range forecast she'd seen earlier in the day, and one word came to mind (well, actually it wasn't one word, like rain, or sleet or snow, but two words, just like the one door that had become two doors on her walk this afternoon, and Rubob's one chimney that had become two chimneys at the hatter's cottage, or for that matter, the hatter's cottage that had become two hatter's cottages -- so there was indeed an element of conjuring in Tine's magical thoughts). Tine's mind most definitely was wandering; either that, or she was seeing double, she thought. But to get back on track, those two words were: "ice pellets." It was the most curious forecast Tine had ever seen, and if you think she's imagining things, like cabbages in the moonlight, well, here's the forecast, plain for all to see:

The more Tine's thoughts settled on those ice pellets, the more those ice pellets settled on Tine. She began to shiver, and even to doubt whether she might be able to take a walk with Rubob tomorrow. "I don't think I've taken a walk in ice pellets before," she thought.

Earlier in the day, Tine had asked Rubob about the forecast for ice pellets.

"That's hail," Rubob said.

"Why didn't they say 'hail,' then, Rubob?"

"I don't know, Tine," Rubob had replied.

At dinner, Tine had told her niece, godchild and good friend, Snowy, about the forecast, and Snowy had looked just as flummoxed as Tine had been when she first saw the forecast.

"Ice pellets? They're bigger than hail. That must be it," Snowy said. "I hope school is canceled."

"I hope so, too," said Whiny, who was enjoying her own dinner, an iced donut and an oatmeal cookie.

Tine, of course, didn't go to school -- hadn't in quite a while, or maybe hadn't ever -- but she was afraid that if school were canceled, pleasant afternoon walks might be canceled, too.

Tine lay in bed feeling like an ice pellet, or maybe even two ice pellets, or perhaps even three ... five .... eight ... thirty-four ... fifty-five, three hundred and seventy-seven ice pellets. Tine's mind filled with ice pellets, and Tine's mind being what it is, it wasn't long before it was filled with pleasant, crystalline ice pellets.

That might sound repetitive, and so it should, because that's really what it is: repetitive. Tine's mind at bedtime becomes something like a minature replicator. Bits and pieces of Tine's walk repeated themselves all over again as she dozed off in her warm bed, seeming every bit as real and filling up her mind every bit as much as they did during her afternoon walk. "Have you ever looked at a cabbage in the moonlight," Tine thought. "Well, it's such a lovely, astounding, leafy, bountiful thing, taking shape in the dark soil under the moonlight, that the mind itself can't help feeling itself become a cabbage in the moonlight for a moment."

It might seem that Tine was overly weary and overly chilly again, as she often is after long winter walks, and that her mind was wandering aimlessly again (or "aimessly," as Tine thought sleepily) . But while she was weary, she wasn't overly weary. She was comfortably weary, because she was in her cozy bed. If she had explained it to Rubob, she might have said that she was appropriately weary, perhaps seventy percent weary (because Rubob sensibly likes to quantify things). And she definitely wasn't chilly; she was warm and content. And what's more, she knew exactly what she was thinking; her mind may have been wandering, but not aimessly. A mind, like the moon, or even like a walker, is expected to wander; it's part of being a mind. Thoughts of cabbages in the moonlight led to thoughts of doorways in the daylight, of pendants (those things over doorways on garrison Colonials), of stones (those things in walls), and of holiday ornaments (those "hideous" things, as Rubob might say if he was in a Scrooge-like frame of mind).

All these pleasant images, these late-night conjurings in Tine's bed, were chased aside, though, when Tine's thoughts turned to where her walk might take her tomorrow. She recalled the long-range forecast she'd seen earlier in the day, and one word came to mind (well, actually it wasn't one word, like rain, or sleet or snow, but two words, just like the one door that had become two doors on her walk this afternoon, and Rubob's one chimney that had become two chimneys at the hatter's cottage, or for that matter, the hatter's cottage that had become two hatter's cottages -- so there was indeed an element of conjuring in Tine's magical thoughts). Tine's mind most definitely was wandering; either that, or she was seeing double, she thought. But to get back on track, those two words were: "ice pellets." It was the most curious forecast Tine had ever seen, and if you think she's imagining things, like cabbages in the moonlight, well, here's the forecast, plain for all to see:

The more Tine's thoughts settled on those ice pellets, the more those ice pellets settled on Tine. She began to shiver, and even to doubt whether she might be able to take a walk with Rubob tomorrow. "I don't think I've taken a walk in ice pellets before," she thought.

Earlier in the day, Tine had asked Rubob about the forecast for ice pellets.

"That's hail," Rubob said.

"Why didn't they say 'hail,' then, Rubob?"

"I don't know, Tine," Rubob had replied.

At dinner, Tine had told her niece, godchild and good friend, Snowy, about the forecast, and Snowy had looked just as flummoxed as Tine had been when she first saw the forecast.

"Ice pellets? They're bigger than hail. That must be it," Snowy said. "I hope school is canceled."

"I hope so, too," said Whiny, who was enjoying her own dinner, an iced donut and an oatmeal cookie.

Tine, of course, didn't go to school -- hadn't in quite a while, or maybe hadn't ever -- but she was afraid that if school were canceled, pleasant afternoon walks might be canceled, too.

Tine lay in bed feeling like an ice pellet, or maybe even two ice pellets, or perhaps even three ... five .... eight ... thirty-four ... fifty-five, three hundred and seventy-seven ice pellets. Tine's mind filled with ice pellets, and Tine's mind being what it is, it wasn't long before it was filled with pleasant, crystalline ice pellets.