'What's the Hurry, Henny Penny?'

" 'Where do you travel so fast, Chicken Little?" asked Henny Penny,' " Tine said to Rubob, chattering away as they set off in the vehicle for their walk.

" 'Ah, Henny Penny,' said Chicken Little, 'the sky is falling, and I must go and tell the king.'

'How do you know that the sky is falling, Chicken Little?' asked Henny Penny.

'I saw it with my eyes, I heard it with my ears, and a bit of it fell on my head,' said Chicken Little. "

Tine and Rubob required the vehicle for today's walk because Tine wanted to drive to the site of a canal that once ran through the village.

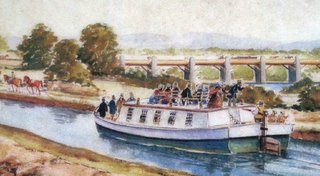

Tine had in her mind a picture of what the canal might look like:

But that must be saved for later, because the story of Tine's walk this afternoon is getting ahead of itself.

For the past few days, she'd been preoccupied with Foone, one of the Africans who lived in the village in the 1840s after taking command of the slave ship Amistad and sailing it to freedom.

Tine was fascinated by the Amistad, which she'd visited in Mystic Seaport, a town as timeless as Tine's own village. She'd been invited aboard the boat by one of the crewmen and even asked to stay for a shrimp dinner (among Tine's favorites). For Tine, who loves everything pertaining to the sea, she might as well have died on the spot and set sail for heaven.

Tine had read that Foone and the other men from the Amistad had farmed in the Meadows down by the river in her village, and after work, before returning home, they'd stopped to swim in a canal basin where boats docked. Foone had drowned swimming in the basin. This past week, Tine and Rubob had visited his gravestone.

This afternoon, Tine thought, she'd visit the canal, or what was left of it. Resting in her lap in the car was an open guidebook (curiously enough, given her meditations on guidebooks the previous night).

"There's an aqueduct, Rubob," she said, "a viaduct or some such thing."

"Why a duck?" Rubob replied. "Why a no chicken?" he asked, quoting Chico Marx. Rubob was driving through fog that was, well, as thick as duck soup. The view of the field on the hillside on their street was quite different from when they walked to the library yesterday afternoon.

"It's a little stuffy in the vehicle," Tine said, "and it smells of oil."

"They changed the oil today, Tine," Rubob said. "

Riding in a car can be somewhat suffocating when one's used to walking in the fresh air, but for Rubob and Tine it was especially suffocating because the electric windows had ceased operating.

"We’ll have to take it back to Henny Penny’s," Tine said.

As they made their way out of the village on its well-trafficked main thoroughfare, Tine said to Rubob, "Look out for Aqueduct Lane on the right."

They drove for more than a mile and thought they'd gone too far, when a bright sign loomed out of the mist.

"That's it, Rubob!" Tine said.

Rubob turned up Aqueduct Lane and parked, and Tine rushed down the road, with a stream following along at the side of the lane.

Rubob and Tine crossed the main thoroughfare and were at once presented with a view of the towpath along the canal.

"Well, I'll be," Tine said.

"Who would have thought?"Rubob said, gazing in wonder at the towpath, the canal to the right of it, and the "berm bank" on the other side. "How'd you come across this, Tine?"

"It's so unexpected, Rubob continued. "We've driven by here hundreds of times, and we knew nothing about it. Yes, the sign was there, but it meant nothing at all to us."

The two walked over to a sign giving the history of the canal. A picture showed a passenger boat on the canal in its heyday, and it looked remarkably like the picture Tine had had in her mind earlier.

"Well, this is a bit of Merrye Olde Englande, isn't it Tine?" Rubob said.

Construction on the canal had begun in 1825, the sign said, and by the 1830s, it was "the state's superhighway."

"Inspired by the Erie canal," Rubob and Tine read, the canal "was the largest engineering project ever attempted in New England." The two pored over the sign, eager to learn more about this surprising sight in the foggy winter woods.

"It was designed to be 'a trade route between New Haven and the towns of central Connecticut towns,' " Rubob read aloud. "Before the canal, 'merchandise had moved slowly in horse-drawn wagons over the region's rough roadways.' "

"Merchandise," Tine said, savoring the word. She had visions of a UPS truck being drawn slowly down the canal by horses. "That's what it's all about in our world: moving merchandise," she thought.

"'Horses hauled the freight and passenger boats at speeds up to 4 mph,' " Rubob said.

On Rubob and Tine's little sailboat, Puffin, Tine thought, Rubob would be inclined to start up the motor at that speed.

"It was dug by hand, using axes, shovels, picks and wheelbarrows," Rubob said.

Tine looked down into the canal, which was filled with enough water from rain and melted snow to appear to be floating the notion that it might resume operations before long.

"The canal was so economical," Tine. "After all, there was a free supply of water."

"Let's follow it to the river, Tine," Rubob said, and the two set off down the path.

"Look, Rubob, the ropes for towing the canal boats," Tine said, pointing up at thick vines hanging from a tree.

"How wide was the canal, Rubob?"

"Twenty feet, the sign said, and 4 feet deep."

The canal bed narrowed and faded in to the mist as they approached the river.

Rubob and Tine soon reached the river, which was blanketed in fog.

At the end of the towpath, there was another sign for Rubob and Tine to pore over, with pictures of the aqueduct that had carried the canal across the river.

It was "built of wood and coated with clay," Tine read from her guidebook, a small blue book written by Ernest Shaw.

"There's something odd about a canal crossing a river," Rubob said.

""Why's that?" Tine asked.

"It seems pointless somehow," Rubob replied, "one waterway suspended over another."

"Look, Tine -- the remains of the old supports," Rubob said, walking over to a pile of sandstone blocks.

Rubob poked around other remains of supports for a while, and Tine found a reflecting pool to gaze into.

The two met up with each other again at the towpath, and Rubob said, almost wistfully, "The time came when the canal wasn't fast enough any longer, Tine. In 1830, there were no railroads competing against it. But in 1848, of course there would be."

That was the year when the Farmington Canal Railroad bought the right of way and converted the towpath into a railbed, Tine had read on one of the signs.

On their way back along the towpath, Tine thought about how Henry David Thoreau had written a thing or two about railroads in "Walden." She couldn't remember what he'd said word for word, but she recalled the spirit of it, the general gist, and that was enough to keep her mind occupied on her way back along the towpath.

"What are you thinking about, Tine?" Rubob asked.

"Nothing, Rubob," Tine said. "Well, something, but I can't quite put it into words."

Readers of this blog, unlike Rubob, needn't be kept waiting for Thoreau's thoughts on railroads, because Tine is home now, and after rummaging through her pile of books on the floor, she managed to retrieve her dog-eared copy of "Walden." Readers can hasten through the mist, taking a faster track, as it were, and join Tine with her book.

"And if railroads are not built, how shall we get to heaven in season?" Thoreau wrote. "But if we stay at home and mind our business, who will want railroads? We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us. ... Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life?"

Thoreau had even been inspired by the railroad to compose a poem:

"What's the railroad to me?

I never go to see

Where it ends.

It fills a few hollows,

And makes banks for the swallows,

It sets the sand a-blowing,

And the blackberries a-growing,

but I cross it like a cart-path in the woods.

I will not have my eyes put out and my ears spoiled by its smoke and steam and hissing."

But getting back to the canal and to Tine and Rubob's walk (which was proceeding unhurriedly, one step after another, with things in their proper sequence): When they were approaching the beginning of the towpath again, Rubob said, "Of course cars and trucks have replaced the railroad now. Trains, too, weren't fast enough."

"But the towpath is a footpath now, Rubob. Maybe there's progress after all," Tine said, skipping ahead (not in time, because Tine is incapable of that, but simply to cross the main thoroughfare).

Back in the vehicle, Tine suggested that they stop at old Mrs. Riddle's estate on the way home, to see it in the mist at dusk.

The roadway into the estate reminded Tine of the canal's towpath.

"It's a towpath for vehicles, Rubob," she said.

They got out of the vehicle and walked up to old Effie Riddle's house -- for that was Mrs. Riddle's first name, Tine had learned from Ernest Shaw's guidebook.

How different the house looked in the mist at dusk.

"It really does seem like the sky is falling, Rubob," Tine said.

"Isn't it something," Rubob said look around him. "Spectral is the word."

"How do you know that the sky is falling? asked Henny Penny," Tine said, chattering to herself again. "Where do you travel so fast."

"I've lost one of my gloves, I think, Rubob," Tine said, stopping in the snow and searching frantically in her pockets. It's probably in the vehicle."

"It's not in the vehicle, Tine," Rubob said.

"How can you be so certain of that?" Tine asked.

"Because I've got it right here," Rubob said, handing it to her with a chuckle and getting in the vehicle. "You keep dropping it behind you, and I keep picking it up. I'm looking out for you, Tine, picking up the lost strands."

The two said their goodbyes to Mrs. Riddle, and as they drove past a house across the street from her estate, Tine pointed out a house to Rubob, one whose bright windows were glowing in the mist. "We could be quite comfortable there, couldn't we?"

"If we stay at home and mind our business, who will want railroads?" Tine thought later in the evening, turning Thoreau's words over in her mind.

"But we didn't stay home today, did we?" she reflected, "and all in all, it was a very pleaant walk."