'Geworfen': Thrown Into the World

Tine and Rubob took a short walk through the woods by the river today, retracing the route they'd taken on their icy walk at the end of December. But spring was in the air, and the treacherous path had been tamed by the warm attention of the sun. The path was clear of ice, but there were still shaded areas in the woods that were covered with a lingering layer of snow.

Tine and Rubob were quiet as they made their way along the path leading to the riverbank. Before they set out, they'd been discussing their sailboat, the doughty little "Puffin," and all the chores they faced in the spring to get her ready for launching. Rubob had endeavored to raise the subject again as they started out on the path, but Tine said, "I can't think about it all now, Rubob."

To her, the snow in the woods represented a reprieve before the arrival of the boat projects in the spring. But despite her best efforts, she, like Rubob, was thinking about the work ahead -- about buying a new dinghy, replacing the halyards, repairing the keel, painting the bottom, polishing the hull, fixing the engine. The list of tasks went on and on, and the warming weather was a sign that the work would have to be faced.

"Look, Tine, two trees growing together," Rubob said.

Tine looked over at the base of the two trunks, standing rooted in the earth, and she thought how the path now provided secure purchase for her feet, and for Rubob's. On the last walk here, they'd had to search for safe places to plant their feet.

"It's like two trees growing from one acorn, Tine -- like twins," Rubob said.

"There's another one, Rubob -- or another two," Tine said. "I wonder what brings them together like that, how they can thrive so close together."

"Is it a case of chance or choice?" Rubob asked. "They're thrown onto the ground as seeds, they put down roots, and that's it. "

"Thrown or fallen?" Tine wondered to herself. She thought of Martin Heidegger's use of the word "thrown" -- "geworfen." We find ourselves thrown into the "thereness" of the world, Heidegger wrote.

Rubob was thinking the same thing: "It's like what your friend Heidegger says, Tine -- how we're thrown into things," he said.

Tine thought how some acorns are scattered about by chance, and how some are brought together.

"Maybe Rubob and I were thrown into the world together -- or at least thrown together in the world," Tine thought. "We put down roots, and that was it."

"Human beings are 'more daring than plant or beast,' according to Heidegger," Tine thought, looking at Rubob standing before the trees. Heidegger quotes the poet Rainer Maria Rilke saying that we "go with this venture," we "will it."

"We made the choice to venture together in this world we've been thrown into," Tine thought, looking at the trees rooted in the ground and reaching for the sky together.

"You'd think it would be easier for a tree to have its own space, so it wouldn't have to share nutrients," Rubob said.

"I'm not quite sure how it is with trees, Rubob," Tine said.

She thought of St. Bernard, who said he'd learned more from trees than he'd ever learned from men. "You will find more in woods than in books; trees and stones will teach you what you can never learn from masters," he wrote.

"Maybe there are advantages in sharing space, Rubob -- a perfect synergy in the forest," Tine said.

With people, the more venturesome ones among us, Heidegger wrote in "Poetry, Language, Thought," "do not venture themselves out of selfishness, for their own personal sake. They seek neither to gain an advantage nor to indulge their self-interest."

To be human, Heidegger wrote, means "to cherish and protect, to preserve and care for."

Tine and Rubob fell back into silence as they followed the winding path through the woods.

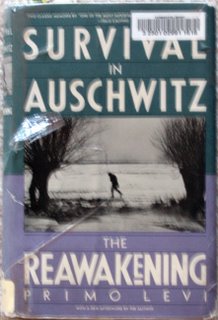

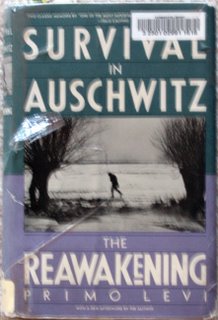

Tine thought of the book she'd been reading, one she'd borrowed from Rubob, Primo Levi's memoirs of Auschwitz -- two memoirs in one, really: "Survival in Auschwitz" and "The Reawakening." In the concentration camp of Buna, the inmates had been compelled to steal from one another to survive with the barest of resources. After the war, on the long journey home, there were more opportunities to work together to survive.

Curiously, Rubob's mind was again on the same thing, because he said, "Have you got to the part in 'The Reawakening' about Primo's friend Cesare, where he sells the brass ring?"

"No, Rubob -- I was just thinking about that book. I remember Cesare selling the shirt with the hole in it, though -- by holding his finger over the hole in the collar while waving the shirt in the sun, 'declaiming its praises.' After selling it for a larcenous price to a man they call 'Big Belly,' they walk slowly to the nearest corner and then run for their lives."

In the infirmary at Auschwitz in the last days of the war, Primo Levi had met the rogue Cesare. Through a wooden wall in the infirmary, Levi had heard Italian being spoken, and he'd found two ill, emaciated Italians, Cesare and Marcello, clinging together for warmth in one bunk. Months later, Levi had run into Cesare again at a Russian camp, and on their journey home Levi had accompanied Cesare on his trading forays in the marketplaces of the towns they passed through.

"Yes, I remember Cesare and the shirt," Rubob said. "Later on, there's the story of the brass ring. Cesare the charlatan buys a ring from a former trading partner. He pays all of four rubles, more than the ring is worth. He then spends his time on a train journey diligently polishing the ring. When the train stops at a village station, Cesare approaches some Russian peasants, holds the ring half hidden against his chest and whispers, 'Gold!'"

"At the moment when the train whistles, preparing to depart, Cesare agrees to part with the ring for 50 rubles and climbs onto the moving train. The swindled peasant shows the ring to his friends, who express their doubts about it. The train starts to slow down for some reason and screeches to a halt. The Russians march alongside the train, looking for Cesare. He hides in a corner of a train car, under a mass of jackets, sacks and blankets. The Russians approach and start banging against the doors of the car, but fortuitously, the train starts up again, in the nick of time. Cesare emerges, Levi writes, ' as white as death.' But he quickly recovers and says, 'Now let them look for me!'"

"He's an odd companion for the honest, bookish Levi, isn't he Rubob?" Tine said. "But then he fell in with another conman, the Mordo the Greek, too."

The Greek was an even stranger companion for Levi on his journey -- a less lighthearted thief than Cesare, grimmer in purpose. Levi described him as "nothing but a rogue, a merchant, expert in deceit and lacking in scruples, selfish and cold."

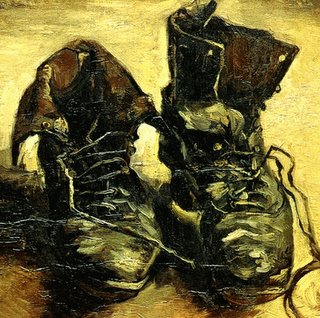

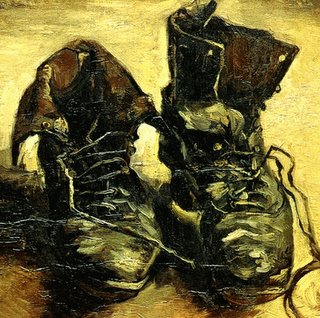

"When war is waging," the Greek told Levi, "one has to think of two things before all others: in the first place of one's shoes, in the second place of food to eat; and not vice versa, as the common herd believes, because he who has shoes can search for food, but the inverse is not true."

"A Pair of Shoes," by Vincent van Gogh

After "work" hours, when the Greek had finished his scheming and trading -- in eggs, shirts and even in women -- he became more cordial, and a flask of wine would sometimes appear unexpectedly from his sack. Warmed by the wine, the Greek would tell Levi his stories of the war.

Tine thought of Levi's comparison of the Greek and Cesare: "An abyss lay between [them]. Cesare was full of human warmth, always, at every moment of his life, not just outside office hours like Mordo Nahum. For Cesare, 'work' was sometimes an unpleasant necessity, at other times an amusing opportunity to meet people, and not a frigid obsession, or a luciferesque affirmation of himself. One of them was free, the other was a slave to himself; one was miserly and reasonable, the other prodigal and fantastic. The Greek was a lone wolf, in an eternal war againt all, old before his time, closed in the circle of his own joyless pride; Cesare was a child of the sun, everybody's friend; he knew no hatred or contempt, was as changeable as the sky, joyous, cunning and generous, bold and cautious, very ignorant, very innocent and very civilized."

"Cesare is more of a friend and partner of Levi's, Rubob," Tine said.

"Levi's falling in with the Mordo the Greek," Tine thought, "was more a case of chance than choice. And while they were often separated on the circuitous journey home, they continued to run into one another. The Greek and Levi -- their journeys somehow became entwined."

Tine and Rubob turned a corner on the path, and in a clearing by the riverbank, they were set upon by four snarling beasts, a group of growling, leaping little terriers. Their owner, a stocky fisherman sitting on the bank, tried to call them off, but the dogs snapped at Tine's heels.

Tine managed to inch her way by them. She usually likes dogs, but caught in the midst of these yapping, sharp-toothed curs, she said, almost involuntarily, "I'm scared of them, Rubob." He coaxed Tine out of the clearning into the woods ahead.

The two soon reached a steep hill leading up to the old railway bridge, and Tine said, "It isn't like last time, when we could barely make it up the hill because of the ice."

"It's not the insurmountable mountain it was, Tine," Rubob said, walking briskly up the slope. "In some ways, it's like the boat. When we first bought it, it seemed like an impossible, endless project to get everything done. But think of how much we've done. It hasn't taken us long to get the knack of things. The daunting ice has melted away, and we're nearing the summit, Tine."

"I think it's because we can work on it together, Rubob, " Tine said. "We do things well together. We weren't thrown together by chance, weren't we?"

"No, Tine,"Rubob said.

As the two made their way along the railway bridge, the view of the river opened out before them.

"It's true what you said about the boat, Rubob," Tine said. "Together we'll be able to get things done in time. With us, it's not like with those trees of yours competing for nutrients. When we're with each other, all resources seem to open out to us. How is that?"

"But it's still all the details that scare me," she said -- "all the things we have to learn to do. All the loose bits and pieces of the projects have been left jangling around in my mind over the winter -- right down to the little plug for the drain in the hot-water heater. They're like the sack of junk that Mordo the Green carries around. I can't keep track of it all. You're good at finding exactly what to do with everything, at thinking through every detail, at coming up with solutions -- like how to fix the keel."

Tine, standing on a concrete bench on the bridge to get a better view over the black iron railing, thought again of Heidegger. There's a danger in being more venturesome, he wrote, but a paradoxical security, too: "The daring that is more venturesome, willing more strongly than any self-assertion ... 'creates' a secureness for us in the Open. To create means to fetch from the source. And to fetch from the source means to take up what springs forth ...."

"I don't think I'm all that good at all with details at all," Rubob said as Tine jumped down from the bench and started back along the bridge toward the path through the woods.

"Why do you say that?" Tine said.

"Well, for one thing, I can't remember anything."

"You remember all the things from your reading. What about all the details from Primo Levi's book? And everything you read about the boat, too," Tine said.

"I don't remember much at all. Sometimes I think, why not just read the first couple of sentences in each paragraph in the books I read? Why waste my time reading every sentence when I forget most of what I read?" Rubob said.

"You remind me of what you say about your durn mother-in-law, Tine said, referring to her mother -- "how she doesn't read and doesn't retain what she does read. But she reads quite a bit and retains a lot of it, doesn't she? And so do you. You're too hard on the Mutti, and too hard on yourself."

"When she called this morning, she was saying that she was reading 'Beach House' or 'Bleak House,' " Rubob said. "I can't even remember which."

"Well, that's a silly thing to say, because you gave her the book, admonishing her not to turn down the corners of the pages," Tine said.

"I asked her whether she usually turned down page corners," Rubob said.

"And she said she did," Tine said, chuckling to herself.

"She's a funny thing," Rubob said. "She was telling me on the phone this morning about her Swiss friend Margaret, who's feuding with one of the women they used to meet on the beach. Has she told you about that?"

"No, Rubob," Tine said.

"Margaret used to be good friends with a woman in their little circle at the beach. One day the woman, who doesn't drive, asked Margaret if she'd take her to the mall. Her husband, she said, didn't like shopping, and so it would be nicer if she and Margaret went together, providing that Margaret drove. Margaret was put out by the request, but she agreed. She then became annoyed when the woman didn't buy lunch for her. That's the least she could have done, Margaret said. Then, when they arrived back at Margaret's place, the friend asked to be driven home, so the husband wouldn't have to pick her up. This was the final straw for Margaret. She drove the friend home, but yelled at her, saying the least she could have done was get her own ride home. From that day on, the two haven't spoken to one another. "

"A sad story, Rubob," Tine said -- "truly heartbreaking."

She thought it all sounded a bit like Heidegger's "Gerede" -- "chatter" or "idle talk."

We've "fallen into the world," Heidegger wrote, and "'fallenness' into the 'world' means an absorption in being-with-one-another, insofar as the latter is guided by idle talk, hunger for novelty ...." In this world of "everydayness," we "fall away from ourselves"; we're left uprooted, "everywhere and nowhere." But from this fallenness, he wrote, we can "strive to return to authentic being."

"I thought of telling your mother," Rubob said, "that she should walk up to Margaret's old friend on the beach, with Margaret in tow, and say something like, 'I was just telling Margaret thus and so, wasn't I, Margaret?' and Margaret would have to speak to her friend, ending the feud."

"I don't think that would work," Tine said. "Margaret's too strong-willed for that, too self-willed. No doubt their paths will cross again before long, as Levi's did with the Greek."

"Maybe that's true, Tine," Rubob said. "I'd be less inclined to leave it all to chance, though."

"Maybe some friendships aren't based on much more than chance," Tine said. "Others, like that between Tchoan and Margaret, are more lasting. They've been friends for years and years, and yet they often have disagreements. We have to cherish and protect our friendships, to preserve and care for them. That's what old Heidegger might venture to add to this conversation."

Tine thought how Heidegger had written that we're thrown into the world with others, and we can't treat others as objects, as "human-things, as they-selfs." As George Steiner put it in his book on Heidegger, the world into which we're thrown has others in it, and being in the world is being-with.

We return to "authentic being" by treating others with "Sorge," with solicitude, Heidegger wrote. And Steiner explained: "Sorge is a concern with, a caring for, an answerability to, the presentness and mystery of Being itself, of Being as it transfigures beings."

Tine heard barking, and she snapped out of her meditation on Heidegger.

"We're approaching the vicious curs again, Rubob," she said.

"Wicious," Rubob said. "Naturally wicious."

"Swine, that's what they are," Tine said. "We'll have to find a detour to avoid the snarling beasts. They're lying in wait around the bend for us human-things."

"Us what, Tine?" Rubob asked.

"Bite-able objects," Tine said. "They want to chomp on the human-things in the woods."

The two made a wide circle around the fisherman and his wretched mutts. Back on the beaten path, they met a man with a golden retriever coming the other way, and Tine told him what lay ahead. "Thanks for the warning," the man said, and he pulled the retriever back on his leash and turned around.

The leader of the pack of terriers, a fat little beast with brown splotches on his white coat, stood on the edge of the clearing by the river and saw Tine off with a few final, peremptory barks. "Yeah, and don't think of coming back!" he seemed to say.

"Grrrr-wooorfen!" Tine growled back at the beast, before hastening along on the path.

"We survived, Rubob," Tine said as they headed home. "We made it out in one piece -- or two really. Two in one, Rubob, like your trees."

At the edge of the wood, Tine thought, "All in all, a very pleasant walk."

Tine and Rubob were quiet as they made their way along the path leading to the riverbank. Before they set out, they'd been discussing their sailboat, the doughty little "Puffin," and all the chores they faced in the spring to get her ready for launching. Rubob had endeavored to raise the subject again as they started out on the path, but Tine said, "I can't think about it all now, Rubob."

To her, the snow in the woods represented a reprieve before the arrival of the boat projects in the spring. But despite her best efforts, she, like Rubob, was thinking about the work ahead -- about buying a new dinghy, replacing the halyards, repairing the keel, painting the bottom, polishing the hull, fixing the engine. The list of tasks went on and on, and the warming weather was a sign that the work would have to be faced.

"Look, Tine, two trees growing together," Rubob said.

Tine looked over at the base of the two trunks, standing rooted in the earth, and she thought how the path now provided secure purchase for her feet, and for Rubob's. On the last walk here, they'd had to search for safe places to plant their feet.

"It's like two trees growing from one acorn, Tine -- like twins," Rubob said.

"There's another one, Rubob -- or another two," Tine said. "I wonder what brings them together like that, how they can thrive so close together."

"Is it a case of chance or choice?" Rubob asked. "They're thrown onto the ground as seeds, they put down roots, and that's it. "

"Thrown or fallen?" Tine wondered to herself. She thought of Martin Heidegger's use of the word "thrown" -- "geworfen." We find ourselves thrown into the "thereness" of the world, Heidegger wrote.

Rubob was thinking the same thing: "It's like what your friend Heidegger says, Tine -- how we're thrown into things," he said.

Tine thought how some acorns are scattered about by chance, and how some are brought together.

"Maybe Rubob and I were thrown into the world together -- or at least thrown together in the world," Tine thought. "We put down roots, and that was it."

"Human beings are 'more daring than plant or beast,' according to Heidegger," Tine thought, looking at Rubob standing before the trees. Heidegger quotes the poet Rainer Maria Rilke saying that we "go with this venture," we "will it."

"We made the choice to venture together in this world we've been thrown into," Tine thought, looking at the trees rooted in the ground and reaching for the sky together.

"You'd think it would be easier for a tree to have its own space, so it wouldn't have to share nutrients," Rubob said.

"I'm not quite sure how it is with trees, Rubob," Tine said.

She thought of St. Bernard, who said he'd learned more from trees than he'd ever learned from men. "You will find more in woods than in books; trees and stones will teach you what you can never learn from masters," he wrote.

"Maybe there are advantages in sharing space, Rubob -- a perfect synergy in the forest," Tine said.

With people, the more venturesome ones among us, Heidegger wrote in "Poetry, Language, Thought," "do not venture themselves out of selfishness, for their own personal sake. They seek neither to gain an advantage nor to indulge their self-interest."

To be human, Heidegger wrote, means "to cherish and protect, to preserve and care for."

Tine and Rubob fell back into silence as they followed the winding path through the woods.

Tine thought of the book she'd been reading, one she'd borrowed from Rubob, Primo Levi's memoirs of Auschwitz -- two memoirs in one, really: "Survival in Auschwitz" and "The Reawakening." In the concentration camp of Buna, the inmates had been compelled to steal from one another to survive with the barest of resources. After the war, on the long journey home, there were more opportunities to work together to survive.

Curiously, Rubob's mind was again on the same thing, because he said, "Have you got to the part in 'The Reawakening' about Primo's friend Cesare, where he sells the brass ring?"

"No, Rubob -- I was just thinking about that book. I remember Cesare selling the shirt with the hole in it, though -- by holding his finger over the hole in the collar while waving the shirt in the sun, 'declaiming its praises.' After selling it for a larcenous price to a man they call 'Big Belly,' they walk slowly to the nearest corner and then run for their lives."

In the infirmary at Auschwitz in the last days of the war, Primo Levi had met the rogue Cesare. Through a wooden wall in the infirmary, Levi had heard Italian being spoken, and he'd found two ill, emaciated Italians, Cesare and Marcello, clinging together for warmth in one bunk. Months later, Levi had run into Cesare again at a Russian camp, and on their journey home Levi had accompanied Cesare on his trading forays in the marketplaces of the towns they passed through.

"Yes, I remember Cesare and the shirt," Rubob said. "Later on, there's the story of the brass ring. Cesare the charlatan buys a ring from a former trading partner. He pays all of four rubles, more than the ring is worth. He then spends his time on a train journey diligently polishing the ring. When the train stops at a village station, Cesare approaches some Russian peasants, holds the ring half hidden against his chest and whispers, 'Gold!'"

"At the moment when the train whistles, preparing to depart, Cesare agrees to part with the ring for 50 rubles and climbs onto the moving train. The swindled peasant shows the ring to his friends, who express their doubts about it. The train starts to slow down for some reason and screeches to a halt. The Russians march alongside the train, looking for Cesare. He hides in a corner of a train car, under a mass of jackets, sacks and blankets. The Russians approach and start banging against the doors of the car, but fortuitously, the train starts up again, in the nick of time. Cesare emerges, Levi writes, ' as white as death.' But he quickly recovers and says, 'Now let them look for me!'"

"He's an odd companion for the honest, bookish Levi, isn't he Rubob?" Tine said. "But then he fell in with another conman, the Mordo the Greek, too."

The Greek was an even stranger companion for Levi on his journey -- a less lighthearted thief than Cesare, grimmer in purpose. Levi described him as "nothing but a rogue, a merchant, expert in deceit and lacking in scruples, selfish and cold."

"When war is waging," the Greek told Levi, "one has to think of two things before all others: in the first place of one's shoes, in the second place of food to eat; and not vice versa, as the common herd believes, because he who has shoes can search for food, but the inverse is not true."

"A Pair of Shoes," by Vincent van Gogh

After "work" hours, when the Greek had finished his scheming and trading -- in eggs, shirts and even in women -- he became more cordial, and a flask of wine would sometimes appear unexpectedly from his sack. Warmed by the wine, the Greek would tell Levi his stories of the war.

Tine thought of Levi's comparison of the Greek and Cesare: "An abyss lay between [them]. Cesare was full of human warmth, always, at every moment of his life, not just outside office hours like Mordo Nahum. For Cesare, 'work' was sometimes an unpleasant necessity, at other times an amusing opportunity to meet people, and not a frigid obsession, or a luciferesque affirmation of himself. One of them was free, the other was a slave to himself; one was miserly and reasonable, the other prodigal and fantastic. The Greek was a lone wolf, in an eternal war againt all, old before his time, closed in the circle of his own joyless pride; Cesare was a child of the sun, everybody's friend; he knew no hatred or contempt, was as changeable as the sky, joyous, cunning and generous, bold and cautious, very ignorant, very innocent and very civilized."

"Cesare is more of a friend and partner of Levi's, Rubob," Tine said.

"Levi's falling in with the Mordo the Greek," Tine thought, "was more a case of chance than choice. And while they were often separated on the circuitous journey home, they continued to run into one another. The Greek and Levi -- their journeys somehow became entwined."

Tine and Rubob turned a corner on the path, and in a clearing by the riverbank, they were set upon by four snarling beasts, a group of growling, leaping little terriers. Their owner, a stocky fisherman sitting on the bank, tried to call them off, but the dogs snapped at Tine's heels.

Tine managed to inch her way by them. She usually likes dogs, but caught in the midst of these yapping, sharp-toothed curs, she said, almost involuntarily, "I'm scared of them, Rubob." He coaxed Tine out of the clearning into the woods ahead.

The two soon reached a steep hill leading up to the old railway bridge, and Tine said, "It isn't like last time, when we could barely make it up the hill because of the ice."

"It's not the insurmountable mountain it was, Tine," Rubob said, walking briskly up the slope. "In some ways, it's like the boat. When we first bought it, it seemed like an impossible, endless project to get everything done. But think of how much we've done. It hasn't taken us long to get the knack of things. The daunting ice has melted away, and we're nearing the summit, Tine."

"I think it's because we can work on it together, Rubob, " Tine said. "We do things well together. We weren't thrown together by chance, weren't we?"

"No, Tine,"Rubob said.

As the two made their way along the railway bridge, the view of the river opened out before them.

"It's true what you said about the boat, Rubob," Tine said. "Together we'll be able to get things done in time. With us, it's not like with those trees of yours competing for nutrients. When we're with each other, all resources seem to open out to us. How is that?"

"But it's still all the details that scare me," she said -- "all the things we have to learn to do. All the loose bits and pieces of the projects have been left jangling around in my mind over the winter -- right down to the little plug for the drain in the hot-water heater. They're like the sack of junk that Mordo the Green carries around. I can't keep track of it all. You're good at finding exactly what to do with everything, at thinking through every detail, at coming up with solutions -- like how to fix the keel."

Tine, standing on a concrete bench on the bridge to get a better view over the black iron railing, thought again of Heidegger. There's a danger in being more venturesome, he wrote, but a paradoxical security, too: "The daring that is more venturesome, willing more strongly than any self-assertion ... 'creates' a secureness for us in the Open. To create means to fetch from the source. And to fetch from the source means to take up what springs forth ...."

"I don't think I'm all that good at all with details at all," Rubob said as Tine jumped down from the bench and started back along the bridge toward the path through the woods.

"Why do you say that?" Tine said.

"Well, for one thing, I can't remember anything."

"You remember all the things from your reading. What about all the details from Primo Levi's book? And everything you read about the boat, too," Tine said.

"I don't remember much at all. Sometimes I think, why not just read the first couple of sentences in each paragraph in the books I read? Why waste my time reading every sentence when I forget most of what I read?" Rubob said.

"You remind me of what you say about your durn mother-in-law, Tine said, referring to her mother -- "how she doesn't read and doesn't retain what she does read. But she reads quite a bit and retains a lot of it, doesn't she? And so do you. You're too hard on the Mutti, and too hard on yourself."

"When she called this morning, she was saying that she was reading 'Beach House' or 'Bleak House,' " Rubob said. "I can't even remember which."

"Well, that's a silly thing to say, because you gave her the book, admonishing her not to turn down the corners of the pages," Tine said.

"I asked her whether she usually turned down page corners," Rubob said.

"And she said she did," Tine said, chuckling to herself.

"She's a funny thing," Rubob said. "She was telling me on the phone this morning about her Swiss friend Margaret, who's feuding with one of the women they used to meet on the beach. Has she told you about that?"

"No, Rubob," Tine said.

"Margaret used to be good friends with a woman in their little circle at the beach. One day the woman, who doesn't drive, asked Margaret if she'd take her to the mall. Her husband, she said, didn't like shopping, and so it would be nicer if she and Margaret went together, providing that Margaret drove. Margaret was put out by the request, but she agreed. She then became annoyed when the woman didn't buy lunch for her. That's the least she could have done, Margaret said. Then, when they arrived back at Margaret's place, the friend asked to be driven home, so the husband wouldn't have to pick her up. This was the final straw for Margaret. She drove the friend home, but yelled at her, saying the least she could have done was get her own ride home. From that day on, the two haven't spoken to one another. "

"A sad story, Rubob," Tine said -- "truly heartbreaking."

She thought it all sounded a bit like Heidegger's "Gerede" -- "chatter" or "idle talk."

We've "fallen into the world," Heidegger wrote, and "'fallenness' into the 'world' means an absorption in being-with-one-another, insofar as the latter is guided by idle talk, hunger for novelty ...." In this world of "everydayness," we "fall away from ourselves"; we're left uprooted, "everywhere and nowhere." But from this fallenness, he wrote, we can "strive to return to authentic being."

"I thought of telling your mother," Rubob said, "that she should walk up to Margaret's old friend on the beach, with Margaret in tow, and say something like, 'I was just telling Margaret thus and so, wasn't I, Margaret?' and Margaret would have to speak to her friend, ending the feud."

"I don't think that would work," Tine said. "Margaret's too strong-willed for that, too self-willed. No doubt their paths will cross again before long, as Levi's did with the Greek."

"Maybe that's true, Tine," Rubob said. "I'd be less inclined to leave it all to chance, though."

"Maybe some friendships aren't based on much more than chance," Tine said. "Others, like that between Tchoan and Margaret, are more lasting. They've been friends for years and years, and yet they often have disagreements. We have to cherish and protect our friendships, to preserve and care for them. That's what old Heidegger might venture to add to this conversation."

Tine thought how Heidegger had written that we're thrown into the world with others, and we can't treat others as objects, as "human-things, as they-selfs." As George Steiner put it in his book on Heidegger, the world into which we're thrown has others in it, and being in the world is being-with.

We return to "authentic being" by treating others with "Sorge," with solicitude, Heidegger wrote. And Steiner explained: "Sorge is a concern with, a caring for, an answerability to, the presentness and mystery of Being itself, of Being as it transfigures beings."

Tine heard barking, and she snapped out of her meditation on Heidegger.

"We're approaching the vicious curs again, Rubob," she said.

"Wicious," Rubob said. "Naturally wicious."

"Swine, that's what they are," Tine said. "We'll have to find a detour to avoid the snarling beasts. They're lying in wait around the bend for us human-things."

"Us what, Tine?" Rubob asked.

"Bite-able objects," Tine said. "They want to chomp on the human-things in the woods."

The two made a wide circle around the fisherman and his wretched mutts. Back on the beaten path, they met a man with a golden retriever coming the other way, and Tine told him what lay ahead. "Thanks for the warning," the man said, and he pulled the retriever back on his leash and turned around.

The leader of the pack of terriers, a fat little beast with brown splotches on his white coat, stood on the edge of the clearing by the river and saw Tine off with a few final, peremptory barks. "Yeah, and don't think of coming back!" he seemed to say.

"Grrrr-wooorfen!" Tine growled back at the beast, before hastening along on the path.

"We survived, Rubob," Tine said as they headed home. "We made it out in one piece -- or two really. Two in one, Rubob, like your trees."

At the edge of the wood, Tine thought, "All in all, a very pleasant walk."